Recognizing the Moon dust could be one of the biggest problems facing lunar colonists, NASA’s Space Technology Mission Directorate is conducting research in the Mojave Desert to find ways to cope with the ubiquitous substance.

Measuring dust ejecta. One project involves a sensor for measuring the ejecta — gravel, small rocks, and lots of dust — that shoot out from the landing zone when a vehicle lands on the Moon. “This can cause widespread damage from sandblasting spacecraft surfaces and solar cells to actually striking and breaking optical sensors or other instruments, says Philip Metzger, a planetary physicist at the University of Central Florida.

“Having ejecta sensor data from actual lunar missions can help us improve those recommendations and will also help us protect the new spacecraft we’re sending to the Moon and even spacecraft orbiting around it – all of which is important not just to the U.S. but to the international space community as well,” Metzger said in a NASA publication. “And then we can develop physics equations that are truly predictive to inform mitigation strategies.”

“Having ejecta sensor data from actual lunar missions can help us improve those recommendations and will also help us protect the new spacecraft we’re sending to the Moon and even spacecraft orbiting around it – all of which is important not just to the U.S. but to the international space community as well,” Metzger said in a NASA publication. “And then we can develop physics equations that are truly predictive to inform mitigation strategies.”

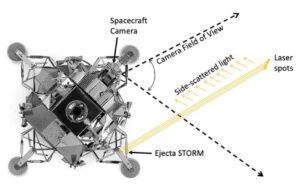

In an upcoming test flight, Metzger’s team will affix their Ejecta STORM sensor to a Zodiac vertical takeoff and landing system with simulated lunar soil placed beneath. The sensor will shine four lasers into the blowing dust cloud.

“When you do a lunar mission, you really get one chance — a period of about 30 seconds — to get the measurements you need,” he said. “So you don’t want to waste that. You have to do field testing to make sure you’ve validated all the different aspects of the sensor that you can.”

Dust collector. A second project, PlanetVac from Honeybee Rotobotics, will test a device that will use gas to initiate suction, transferring a surface sample through a tube, and depositing it in a container to be sent back to Earth for analysis. Previous testing proved the technology could collect more than 300 grams of simulated regolith. The new test will demonstrate the ability to transfer the sample to a container located several feet above the device.

Combining the two projects in the same flight will provide more data than either team would have had they flown solo. The university team’s measurements may help Honeybee better understand how much surface soil can be disturbed while still allowing for a sample dust collection.