Once upon a time the Moon had a magnetic field, and it was likely stronger than Earth’s is today. That field, generated by a powerful dynamo in the Moon’s core, petered out about one billion years ago.

Once upon a time the Moon had a magnetic field, and it was likely stronger than Earth’s is today. That field, generated by a powerful dynamo in the Moon’s core, petered out about one billion years ago.

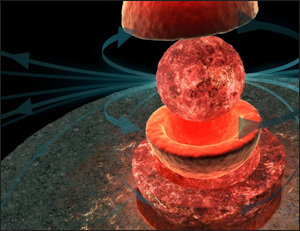

The latest theory, propagated by MIT scientists in the journal Science Advances, suggests that crystallization of the Moon’s inner iron core stirred the electrically charged fluid and produced the dynamo.

“The magnetic field is this nebulous thing that pervades space, like an invisible force field,” says Benjamin Weiss, professor of earth, atmospheric, and planetary sciences at MIT. “We’ve shown that the dynamo that produced the moon’s magnetic field died somewhere between 1.5 and 1 billion years ago, and seems to have been powered in an Earth-like way.”

Most studies of lunar magnetism have been based on rock samples from the Apollo missions; most of the ancient rocks are estimated to be thee to four billion years old. When they were spewed out as lava, their microscopic grains aligned in the direction of the Moon’s magnetic field. Lunar rocks whose magnetic histories began less than three billion years ago do not show such alignment, which suggests that lunar vulcanism had largely ceased by that time.

The MIT scientists theorize that the early Moon was much closer to the Earth than it is today, and much more susceptible to its gravitational effects. In a phenomenon known as “precession,” the solid outer shell of the cooling Moon wobbled in response to the Earth’s gravity. The wobbling stirred up the fluid in the core, the way swishing a cup of coffee stirs up the liquid inside, explains MIT News.

As the moon moved slowly away from the Earth, the precession effect decreased, weakening the dynamo and the magnetic field. About 2.5 billion years ago, core crystallization became the dominant mechanism by which the lunar dynamo continued, producing a weaker magnetic field that continued to dissipate as the moon’s core eventually fully crystallized.